The Oracle of Delphi: Wisdom or Manipulation?

Prediction Is Very Difficult, Especially About the Future

By TheScribesQuill, for History Rhymes

“Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future,” Mark Twain once quipped, and history murmurs agreement. The Oracle of Delphi spoke in riddles, and empires fell. In ancient Greece, this priestess of Apollo shaped destinies with cryptic prophecies—kings like Croesus heard “a great empire will fall” and marched to war, only to lose his own. Was the Oracle divine wisdom or a master manipulator? With a skeptic’s eye, let’s unravel the past and ask: who’s pulling our strings today?

A Voice of the Gods—or a Political Pawn?

The Oracle at Delphi, perched on Mount Parnassus, was Greece’s spiritual center for centuries. Established around the 8th century BCE and reaching its peak influence between then and the 4th century BCE, the sanctuary was dedicated to Apollo after he purportedly slew the serpent Python there, claiming the site from earlier earth deities like Gaea. Leaders from across the ancient world sought her guidance, often hearing vague prophecies that could mean anything. The Oracle, known as the Pythia—a woman over 50 years old, living chastely and selected for her role—would enter a trance-like state in the temple’s inner chamber, possibly induced by inhaling ethylene gases from geologic fissures beneath the site, according to modern geological theories. She sat on a sacred tripod, chewed laurel leaves, and delivered utterances interpreted by priests into ambiguous verse.

Croesus of Lydia (c. 560 BCE) famously tested oracles by asking them to describe his distant actions—only Delphi correctly identified him cooking a tortoise and lamb in a bronze pot. Emboldened, he inquired about attacking Persia and received: “If Croesus goes to war he will destroy a great empire.” However, the oracle warned that: “when a mule becomes king of the Medes, Croesus should flee rather than fight.” Croesus dismissed this as impossible, assuming no mule (a sterile hybrid animal, typically the offspring of a horse and donkey) could ever rule, and proceeded with his attack. After his defeat in 547 BCE and capture by Cyrus the Great, Croesus sent envoys to reproach the oracle for misleading him. The Pythia clarified that the prophecy had been fulfilled: Cyrus himself was the metaphorical “mule,” as he was of mixed heritage (half-Mede, half-Persian).

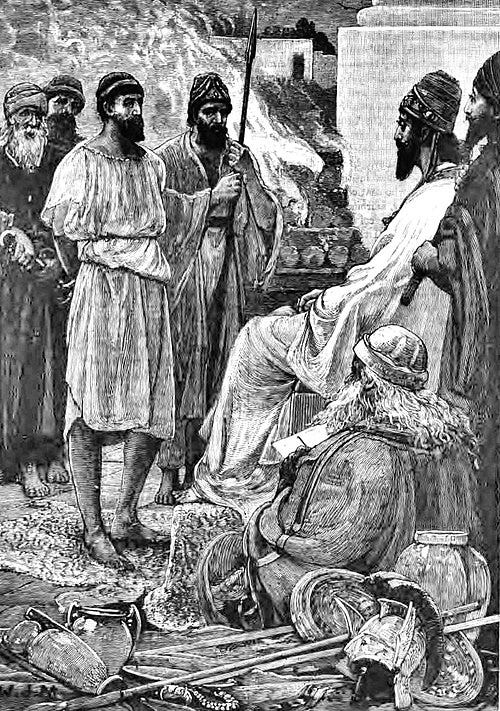

Croesus of Lydia led before Cyrus the Great on the capture of Sardis, c. 546 BC

Coincidence? Or did the Oracle, backed by priests with political agendas and a network of informants, play a long game? Other examples abound: In 480 BCE, amid Xerxes’ Persian invasion, Athens was told to trust a “wooden wall” for salvation. Themistocles interpreted this as their navy, leading to the decisive victory at Salamis despite the city’s sacking. Sparta, consulting before the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE, heard that victory was theirs if they fought mightily, bolstering their resolve. Even Philip II of Macedon was advised, “With silver spears you may conquer the world,” prompting him to seize mines and fund his expansions. Echoes from the past suggest: divine or not, the Oracle knew how to hedge her bets, influencing colonization, wars, and laws while amassing wealth from offerings. Its power waned under Roman rule, with the last recorded prophecy around 393 CE when Emperor Theodosius I banned pagan practices.

Socrates’ Skeptical Eye

Socrates’ friend Chaerephon consulted the Oracle of Delphi in the mid-5th century BCE, asking if any man was wiser than Socrates—only to hear, “No one is wiser.” Puzzled, Socrates set out to test this enigmatic proclamation by interrogating prominent Athenians, from politicians to poets and craftsmen, in a methodical process of questioning that exposed their unfounded claims to knowledge while highlighting his own awareness of ignorance. This pursuit fulfilled the oracle’s wisdom by demonstrating that genuine insight begins with recognizing one’s limitations, all while embodying the Delphic maxim “know thyself” inscribed at the temple. Socratic irony embraced the oracle’s ambiguity rather than mocking it, challenging blind faith in prophecies through relentless critical inquiry over divine riddles. If Socrates were around today, he’d likely scoff at our modern “oracles.” Are we, like Croesus, hearing what we want to hear, or projecting our biases onto opaque systems?

Josef Abel 1807 Socrates teaching his disciples

Modern Oracles, Same Old Tricks

Today’s Delphic voices are everywhere: political pundits predict elections, AI forecasts markets, yet both often fail spectacularly—though successes in areas like drug discovery and climate modeling remind us they’re not all smoke and mirrors. The 2016 U.S. election polls were wrong—Trump won despite odds. AI stock predictions tanked in 2022’s market dips, and this trend continued through 2025, with reports indicating that 30-75% of generative AI projects fail, often due to strategic misalignments rather than technological shortcomings. Elon Musk once noted that “the most entertaining outcome, especially if ironic, is the most likely,” echoing the ironic twists in Delphic prophecies like Croesus’ downfall. Lessons from antiquity warn: manipulation dressed as wisdom is timeless. We’re still falling for riddles, just with fancier tech.

Contemporary discussions draw direct parallels, likening AI’s predictive algorithms to the Oracle’s ambiguity. For instance, large language models like those from OpenAI and Google exhibit strategic reasoning in simulations, such as evolutionary Prisoner’s Dilemmas, where they predict opponents and weigh outcomes—much like the Pythia’s “HUMINT” (human intelligence gathering practices employed by the priests). Projects like OpenAI’s rumored Q* algorithm, speculated to blend search and learning akin to AlphaGo and with rumors persisting into 2025 around evolutions like Project Strawberry, aim to verify reasoning step-by-step, mirroring how Delphic priests interpreted trance utterances. Yet, as with the Oracle’s gas-induced visions, AI’s “black box” nature invites skepticism: are these systems truly prescient, or just exploiting patterns in data, prone to ironic failures?

What’s the Past Muttering Now?

The Oracle of Delphi taught us that power loves ambiguity—vague words let others take the fall, allowing priests to claim credit for any outcome. Scientific views today suggest the Pythia’s prophecies stemmed from geologic vapors or psychological suggestion, not divinity, underscoring how context shapes interpretation. Whether it’s a priestess in 560 BCE or a tech visionary in 2025, the game’s the same: oracles thrive on our desire for certainty in uncertainty. So, what’s history whispering to us? Be wary of those who claim to see the future—they might just be shaping it for their own ends, with irony as their silent partner. As modern AI evolves, embracing “process-supervised” verification to mimic the Oracle’s step-by-step revelations, we must apply Socratic wisdom: question the source, lest we repeat ancient follies.

Enjoyed this tale? Join the Quill’s Circle for more history, philosophy, and mythology that echoes today. Subscribe now!